Water: An Inflationary Risk to the Global Supply Chain

| Author: Keith McLean — Executive Vice-President |

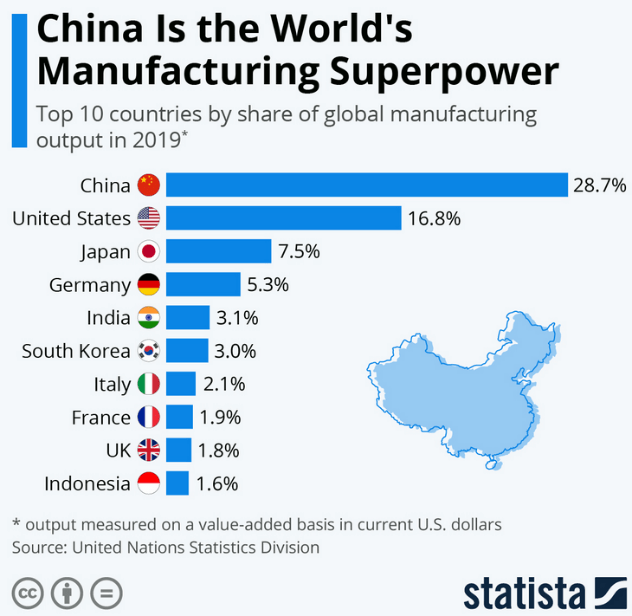

Since the beginning of the COVID crisis in late 2019, China’s important role within the global supply chain has been reinforced on numerous occasions. We have read news stories about impacts to healthcare, packaging, auto manufacturing, computers, and every industry in between. Some of these impacts were caused by supply disruptions in raw materials, some by manufactured components, and some by final goods productions. Regardless of the industry or product being discussed, China seemed to be at the heart of the issue. If it wasn’t before, it is now abundantly clear that China is the world’s factory. As shared by Statista, the growing import of China as a global manufacturing superpower can be observed with data from the United Nations Statistics Division which shows China’s share of global manufacturing has grown to almost 30 percent – 12 percent higher than its nearest competitor.

In the global marketplace, companies have been forced to stay competitive by pursuing ever-higher levels of operational efficiency and return on investment. The pursuit of these efficiencies initially led companies to adopt automation technologies; they later began to outsource some of their low-value-add manufacturing to China and other developing nations. As their competencies broadened and manufacturing skills improved, other valuable aspects of their industrial base and more precise manufacturing began to be outsourced. This outsourcing trend was applauded by the markets, as it led to higher profit margins for the world’s leading companies: they no longer needed to invest in plant and equipment to drive growth or hold large levels of inventory. Alongside this outsourcing was the emergence of a global supply chain management industry that was able to efficiently deliver raw materials, parts, components, and sub-assemblies on a just-in-time basis to ensure maximum capital efficiency throughout the manufacturing process.

After running smoothly for so long, the risks to this fine-tuned system have now been laid bare by a global pandemic. Many investors view COVID impacts as transitory and expect things to rebalance once COVID transitions from a pandemic to an endemic. It is further projected that much of the impetus for the current inflationary episode we are experiencing will also be muted when supply chains return to normal. This was actually my line of thinking until I listened to an Investor’s Podcast discussion with Luke Gromen, who outlined an intriguing longer-term risk to global supply chains: China’s water problem.

“There’s a lot of signs that have begun emerging in the second half of 2021, that the water constraints in China are becoming acute. And to be blunt, if China has a water problem, China has a power problem. And if China has a power problem, the world has a power problem. And the world has an inflation problem, since China is the world’s factory.”

Luke Gromen

As it turns out, this risk has been known for a long time. In fact, China’s water risk was highlighted in 2018 by Charlie Parton of China Dialogue in a great piece called China’s Looming Water Crisis. As this comprehensive report highlights, in 2005, the Minister of Water Resources claimed: “People can’t survive in a desert. To fight for every drop of water or die: that is the challenge facing China.” Also quoted in a related 2013 Economist article, former prime minister Wen Jiabao had claimed that water shortages threaten “the very survival of the Chinese nation.” This same article points out that Beijing’s water table has dropped 100-300 metres since the 1970s. As China Dialogue outlines, the country has 20 percent of the world’s population but only 7 percent of the fresh water. Now that China is manufacturing almost 30 percent of the world’s goods, the potential impacts of an emerging water crisis on the global supply chain need to be considered.

In a recent update to this line of research, Gopal Reddy of Ready for Climatewrote an informative article on the Chinese water crisis. It states that the global economy’s high reliance on China for everything from apparel to chemicals to industrial components means that power and water shortages in China would constrain economic growth across the globe. As an example, 40 percent of the clothing and 70 percent of the footwear sold in the US is sourced from China. The power plants that have sustained this surge in production require water to operate. The people that work in these factories need to be fed, which requires water. Most importantly, water is also needed for the daily lives of Chinese citizens, and there is already an acute shortage of safe, clean drinking water in many parts of the country.

The supply disruptions caused by COVID have shown the world that we may have pushed the global supply chain too far. In order to ensure a international supply chain that runs smoothly, global manufacturers will likely need to hold higher levels of inventory at various points in their production chain. They may also have to “on-shore” some manufacturing processes and produce goods nearer to their end consumers. All of this will either lower return on investment or lead to higher prices in order to protect margins. This could also lead to more demand for raw materials so that manufacturing capacity is protected from the shortage of key materials and can run more efficiently.

Many investors believe these risks are only COVID-related, that we will transition back to more typical supply chains, and inflation will cool down in due time. But has the market considered the inflationary impacts on the global supply chain if a Chinese water crisis were to lead to a more permanent dislocation of manufacturing capacity? The scale of disruption to the global manufacturing base could be acute and the resulting inflation would be much less transitory. We have no way of knowing how this will play out, but a potential Chinese water crisis needs to be integrated into every investor’s portfolio allocation decisions. Adding commodities exposure to provide more inflation protection to a portfolio would be one area to consider in order to hedge this risk. As Charlie Parton notes, “China can print money, but it cannot print water.”

| Still curious? Read more of our insights HERE. |

Leave a comment